IPAC’22 in Bangkok: A Breath of Fresh Air

For a couple of years now, we could only attend the annual International Particle Accelerator Conferences (IPAC) virtually, depending on remote conferencing and web chatting to stay close with the global accelerator community. Now, at the 13th IPAC, we could again walk, observe, attend, speak and mingle in person – and again meet all of our research and industry friends of long years standing.

Scientific research is of great importance in Thailand, so it is no wonder that IPAC’22 was opened by H.R.H. Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn and Prof. Prapong Klysubun of the Synchrotron Light Research Institute. The latter, a scientific power-house building a modern synchrotron light facility in Thailand, was the event’s organiser and main host.

High Energy Physics on the Road-map

The Large Hadron–Electron (LHC) collider at CERN has been running since 2010 and has contributed critical information for our better understanding of the fundamental laws of physics. As most particle physicists today agree that the Stand-ard Model of Physics (SMP) is incomplete, the race is on to discover and prove inconsistencies between the SMP and measurements in experiments.

Higher energies of particle collisions will be needed to push the experimental envelope, and several research organisations besides CERN are planning next-generation colliding accelerators than are larger than the current masterpiece, the LHC. Scientists and engineers working In HEP (High Energy Physics) speak of the four main pillars of development – FCC, CLIC, CEPC and ILC.

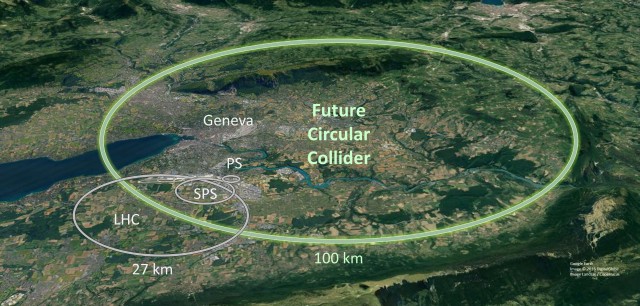

The FCC (Future Circular Collider), with a circumference of 100 km in Geneva, will consist of a double ring either of a highest-luminosity high-energy lepton collider (FCC-ee) or an energy-frontier hadron collider (FCC-hh).

On the other hand, CLIC (Compact Linear Collider) is being planned as an addition to CERN’s existing accelerator installation. It will collide electrons and positrons head-on at energies of up to several TeV and is intended to be built and operated in three stages, at collision energies of 380 GeV, 1.5 TeV and 3 TeV, respectively, for a site length ranging from 11 to 50 km.

The CEPC (Circular Electron Positron Collider) is a large international scientific facility proposed by the Chinese particle physics community that will be geared towards precision measurements. In its first phase, it will have a maximum centre-of-mass energy of 240 GeV, while in its second phase, it will be upgraded to a Su-per Proton-Proton Collider (SppC), enclosed in the same 100-kilometre under-ground tunnel.

The Kitakami highland in Japan is the proposed location of the ILC (International Linear collider) which is a HEP facility which will at first consist of two 11-km long superconducting) main linacs for electrons and positrons. Initially, ILC will enable collisions at centre-of-mass energy at around 250 GeV.

The common thread of all the mentioned projects is that they are still in the preparatory stages and progressing with deliberation and care. The consensus at IPAC’22 was that the ideas within the projects would have to ripen some more, also considering new technologies and industry solutions which will optimise the implementation and cost.

At the Forefront, a Pipeline of 4G Light Sources

In recent years, the number of fourth-generation (4G) light-source research projects in preparation has increased significantly – in the next-decade pipeline are now around fifteen projects. The community is talking about a possible bottleneck in the supply chain of the necessary accelerator parts, components and sub-systems within the next five years or even longer.

At IPAC’22, the general opinion was that modern particle accelerators would require more complex control systems, diagnostics, suites, and special computing tools and solutions, such as artificial intelligence implementations.

One of the most popular types of the latter is machine learning (ML) which can be taught the basic physics ”behaviour“ of accelerator operations to optimise both performance-tuning and everyday performance of particle accelerators based on device data gathered and learned.

Artificial Intelligence and Accelerators

Neural networks are often used in ML to model the actual accelerator and its beam dynamics – implementing real-time learning for beam alignment and other types of accelerator optimisations.

Engineers are already using conventional simulation tools to train the neural network models to perform as accelerator surrogates. The latter’s neural networks can be run in real-time on, for example, desktop computers to simulate to assess beam-dynamics behaviour.

The scientific accelerators being devised today pose greater demands on their data networks and hardware performance. As these will be the backbone for the implementation of the necessary new technologies and accompanying tools, future-proofing of networking and hardware is one of the items on the top of the list of accelerator control architects.

Closer integration of good engineering practices in science and industry is needed, which is reflected in the growing importance of the industrial session at IPAC from year to year. IPAC’22 emphasised the importance of science in the industry even more.

IPAC is Still King of Big Physics

I found the virtualities of the two online IPACs – in 2020 and 2021 – to work fine for me and enable good enough communication with contacts and event participants. Nevertheless, nothing can compare with the compelling commotion of a live event!

Compared with pre-Covid-19 times, the number of this year’s participants was slightly less – we were missing many friends from the United States and China, probably due to the travel-related rules and conditions regarding the pandemic. Nevertheless, slowly but surely, IPAC is returning to its “analogue normal”.

A particular thrill was in the air during the whole conference of 2022, and it was not only because it was one of the first in-person international conferences after two years of online. Namely, it was quite evident that the organiser did an excellent job.

The venue was spacious, and the exhibitions were comfortable, with many little islands for discussion. It was also very kind of the hosts to provide food and drinks at the location. IPAC in Thailand evolved in a gentle yet constructive and orderly manner. Possibly this year’s event was one of the best organised IPACs ever!

The wider surroundings of IPAC’22’s venue, Bangkok, added colour and thrill to our experience. But it was the proceedings at the event itself that proved, once again, that IPAC is the place to be for all who live for Big Physics projects!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rok Hrovatin joined Cosylab in 2015 and has applied his vast experience gained in industry and in the quality and standards arena to identify appropriate control system solutions for unique problems in the world of particle accelerators and big physics.

In his free time, Rok enjoys cycling, sailing, swimming – or just some working around his house. Anything is good as long as he moves his bones. He feels that his leisure time is always too short, but he always enjoys whatever free time he has. Most of all he likes spending quality time with his grandkids.